|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Millions of images collected from Sonoma County backyard trail cams

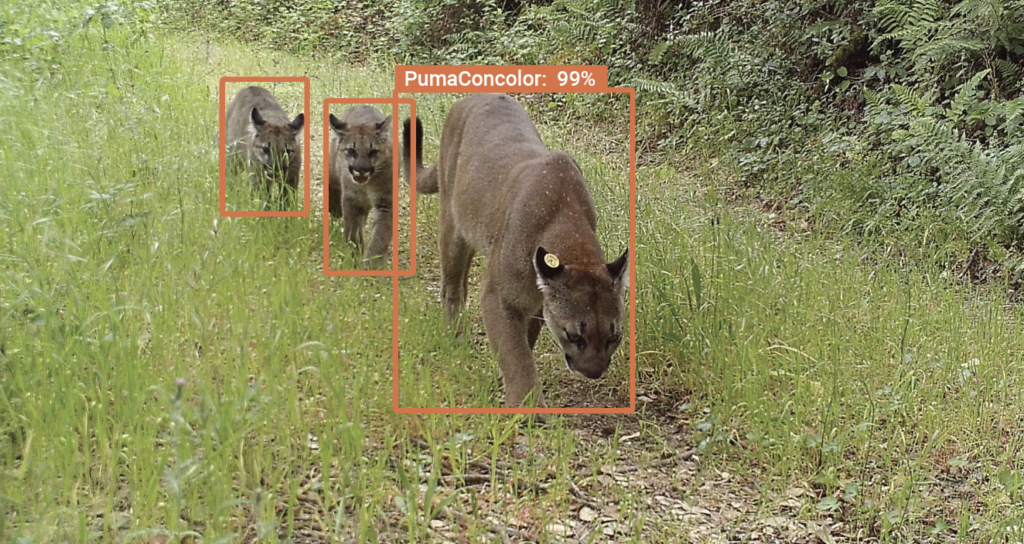

A black bear bumbles by at 2:00 a.m. A mountain lion sniffs around at dusk. A quail family toddles past, pecking the dirt for dinner.

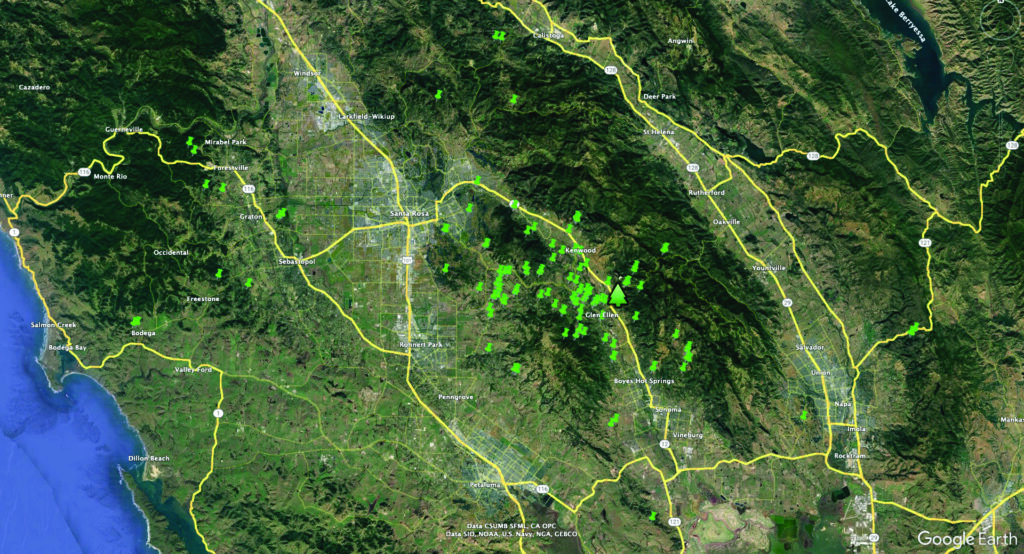

Four million clicks of trail cameras set about the San Francisco North Bay Area by Audubon Canyon Ranch’s Trail Camera Project have captured creatures of all shapes, sizes, and nocturnality since 2018. Researchers want to know: What array of critters live here? How many of them, and what are they up to in this human-dominated landscape? To answer these questions, the images need to be analyzed and categorized – a task too daunting for any human (or a few) alone.

Enter: artificial intelligence

Data experts from Conservation AI, an effort organized by Liverpool John Moores University, aim to harness machine learning for conservation projects. Anyone collecting images from camera traps, drones, and other media can upload them to the Conservation AI site for automatic classification.

The researchers behind the Trail Camera Project were thrilled to learn Conservation AI could help them make sense of their enormous collection of images. The project launched nearly six years ago with just a few cameras and quickly grew in popularity. By the end of 2023, the project included over 140 cameras across Sonoma County. Project Coordinator Kate Remsen and a crew of over 20 volunteers collect images every few weeks from the cameras placed in semi-rural backyards and private properties.

The number of images quickly became a time management nightmare. The small nonprofit research team did not have the time or resources to record and classify each species to extract meaningful data from the collection of images. “The lack of analysis means that we’re potentially missing something important and simply sitting on this valuable mountain of data. It’s been frustrating not seeing anything come of the data,” says Remsen.

The data deluge in conservation science

The problem of collecting more images than can be analyzed in conservation science is often called “data deluge” in the field. With advancements in technology making it easier and more affordable to capture vast amounts of image data via camera traps, satellite imaging, and drones, new challenges have emerged:

- Resource constraints: Conservation organizations often lack the resources, both in terms of finances and human capital, to manually analyze every image collected.

- Time-intensive analysis: Manually analyzing large volumes of images is incredibly time-consuming and may not be feasible given limited resources and timeframes.

- Technological limitations: Existing automated image analysis tools may not be sophisticated enough to accurately process and classify all the images, especially when dealing with complex ecosystems and species.

- Data management: Storing, organizing, and managing large datasets of images pose logistical challenges, including issues related to data storage, security, and accessibility.

Together, these challenges underscore an opportunity cost: The inability to analyze all collected images effectively means potentially missing valuable insights into species distribution, behavior, habitat health, and other crucial conservation-related information.

Technology and collaboration come together

Addressing this problem requires a combination of technological advancements, such as the development of more efficient and accurate automated image analysis like Conservation AI, as well as increased collaboration between conservation organizations, researchers, and technology experts to optimize data management strategies and prioritize analysis efforts.

Remsen can relate to the concept of data deluge. “As coordinator of the Trail Camera Project, I often feel overwhelmed by the number of images,” she shares. “But I enjoy looking through the images to find highlights and deliver them to the landowners. I love hearing their excitement when we find a deer chasing a coyote away from her fawn, or bobcat babies romping around with mom, or of course, the majestic mountain lion.”

Scott Jennings, an Audubon Canyon Ranch ecologist and Remsen’s colleague, adds, “We’re excited to use these new data to give camera sponsors and landowners a deeper understanding of how their land benefits wildlife and how it may be managed to improve those benefits. With this detailed data, we can share more precise information with landowners about which animals are most abundant on their land. And, since we’ll have the same data for a range of private properties as well as our preserves and other protected lands, we’ll also be able to tell how the animal community on a particular property compares to what we might expect from similar habitats. Using that, we will be able to make suggestions about habitat improvements to help the animals that already use their land and encourage new ones to move in. Zooming out, these new data will also help us understand patterns of biodiversity across the whole landscape, so that we can better understand how individual properties contribute to healthy ecosystems across property lines.”

Humans and computers learn together

An explosion of species identification tools, as highlighted by Smithsonian Magazine (like iNaturalist and eBird), are using machine-learning-powered software to recognize a species based on a picture. Conservation AI is different because “we constantly work with organizations to develop tools and refine our AI. Our partners are an integral part of the process, and we develop bespoke models for their specific needs,” explains Carl Chalmers, lead researcher at Conservation AI.

“Conservation AI is helping us in two big ways,” says Nils Warnock, director of conservation science at Audubon Canyon Ranch. “It’s compressing file size without losing resolution to save valuable hard drive space, and using computer learning to identify the animals in the images with 90% accuracy. Combined with Microsoft’s Power BI, we are aiming to cohesively analyze the data collected over the past 5 years and provide detailed annual reports.” The number of images the project had stored on multiple hard drives was unsustainable, until Chalmers created a Python code to reduce image size but not resolution, reducing over 20 terabytes of data to a mere four.

A mutually beneficial relationship

So far, the Trail Camera Project team has uploaded 3.5 million images to Conservation AI. 1.98 million objects have been detected. There is still more work to be done, but the first set of data has been sorted and the Conservation AI machine is undergoing more testing.

A mutually beneficial relationship has emerged: data from the Sonoma trail cameras is helping to train the Conservation AI program to identify North American mammals, and as the AI gets better at recognizing the animals of this region, the Trail Camera Project scientists get more accurate data.

“We’re getting help to analyze our images and we’re helping develop learning for global tool – it’s an absolute win-win,” says Warnock. “It’s great to know that our contribution is helping others facing the same problems.” Chalmers agrees: “I think this partnership is a great example of how two disciplines can work together to help save biodiversity.”

Get involved

Want to contribute to conservation science? Here are ways to get involved:

- Become a trail camera sponsor — If you live in Sonoma County, images collected on your property help us understand overall wildlife densities and distribution in the region and can inspire us all to take steps to coexist with our wild neighbors.

- Learn more about Conservation AI

- Register for an account to help Conservation AI tag images

- Contact Conservation AI for help with your image or video project