Seven months of research may suggest how diet reflects seasonally-available food

True Wild, ACR’s research partner for the Living with Lions program, has connected with the Institute for Wildlife Studies (IWS) and since last May, employed graduate student Jake Harvey to find and record mountain lion prey cache sites. Cache sites are what researchers call “kill clusters” and refer to areas where lions drag or relocate their food. To locate the sites, we look for a grouping of GPS pings from collared lions and then head into the field—or more often, the poison oak covered hillsides—to investigate.

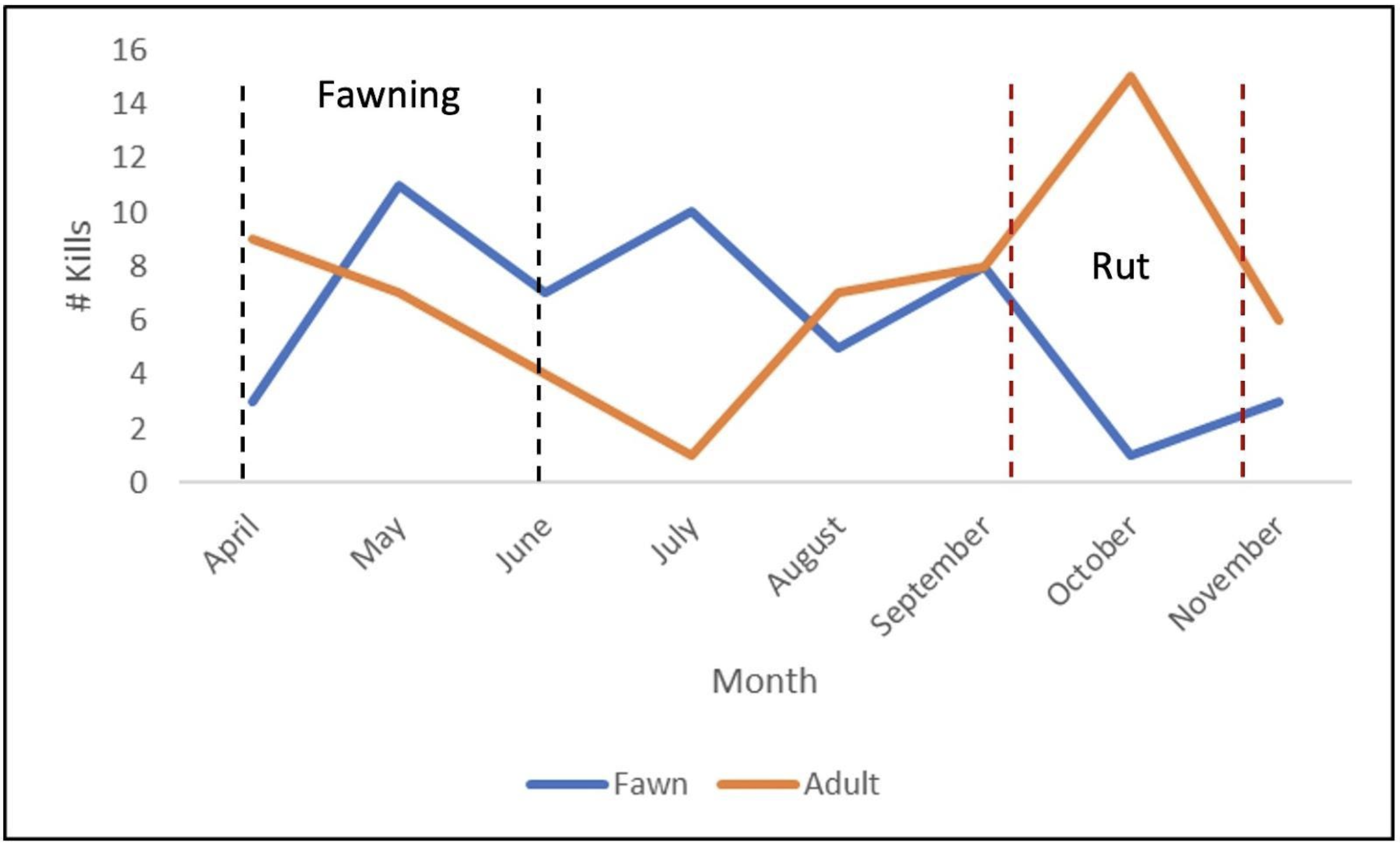

The preliminary data collected so far points to an interesting pattern of prey tied to deer fawning and rutting (or, mating) season.

Fawns in the spring and bucks in the fall: what lions are eating in the North Bay

Of the mountain lions we are tracking in the North Bay, the number of fawns preyed upon outpaces adult deer during the spring fawning season. The fawn take remains high even into mid-summer. Then the trend reverses in the fall, when more bucks are killed than either does or fawns.

It could be that the during the rutting season, the bucks are highly distracted looking for mates and are more vulnerable to the stealthy movements of mountain lions. This is also the period where most deer are killed through vehicle strikes.

Between May–November 2021, Jake headed into the field to investigate nearly 200 clusters. Deer topped the list of species recorded at caches (108), followed by livestock (40), coyote (5), boar (5), birds (7), and less than five each of opossum, cat, squirrel, raccoon, and grey fox. During this period, the livestock numbers reported higher than previous data sets, possibly due to a male mountain lion (P24) in the Healdsburg area who was depredating unsecured livestock over the course of several months; that lion was later killed. The number of livestock versus deer is also high due to several incidents where more than one livestock animal was killed in a single event—something that would rarely happen with wild prey.

Update of mountain lion deaths: conflict issues for some, unknown cause for others

On a somber note, also during this period between May and November, five of the 13 lions tracked by Living with Lions died and another lion (possibly the cub of male lion P31) was killed after being struck by a car west of Sebastopol. In more detail, one lion was euthanized due to poor heath, one was killed after depredating livestock, and three died of unknown health related causes. Tests are being conducted to establish the possible cause of death.

Living with Lions tracks and studies mountain lions in the North Bay to better understand their spatial ecology within suburban and rural landscapes, as well as to raise awareness of these species and how they impact prey.

As we look into the causes for these recent lion deaths, we also want to offer a message of hope: studying these apex predators requires compassion for their role in the greater, complex ecological communities that we share with them. We also look forward to learning more from this recent diet study and sharing our findings.

“Each mountain lion overlaps with thousands of landowners in Sonoma County. Our backyards literally hold the keys to conservation for top carnivores like mountain lions.” —Quinton Martins, True Wild