Do coastal California Great Egrets migrate?

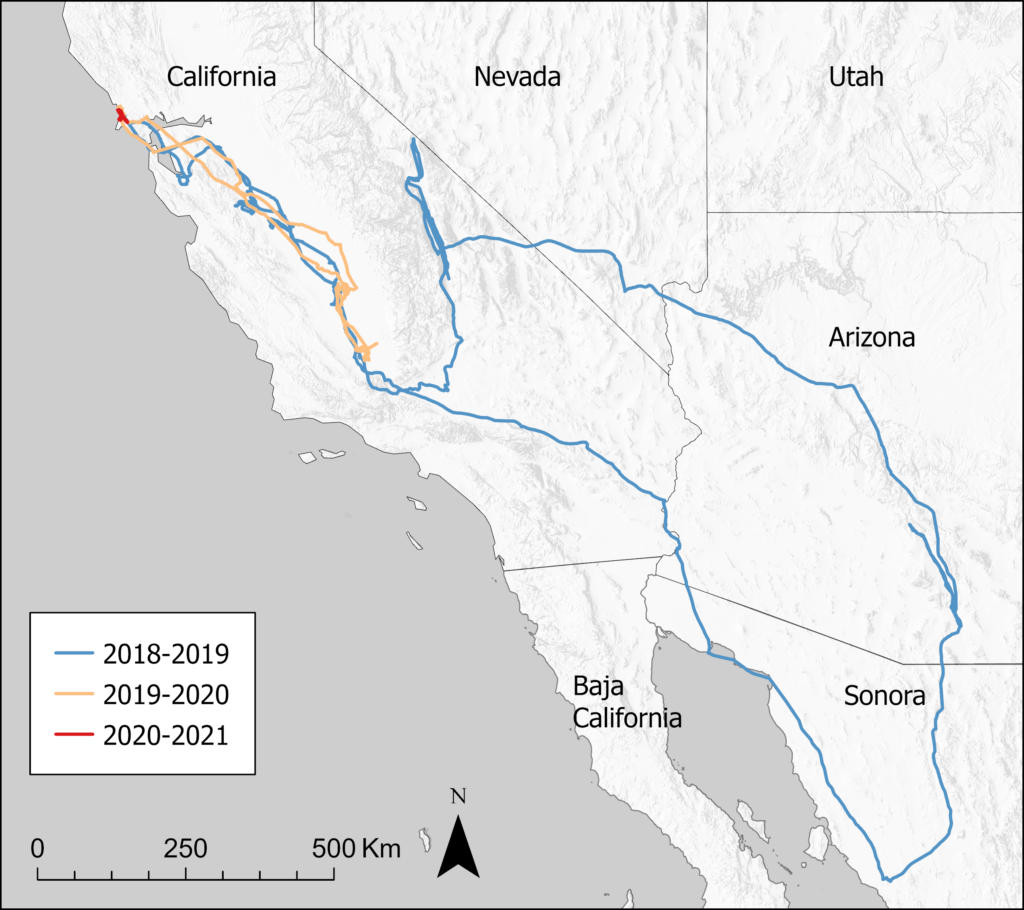

Knowing where animals move throughout their lives is critical for protecting the habitats they rely on. Great Egrets are known to migrate long-distance: studies in eastern North America, Europe, and Australia show they frequently fly 1,000km (621mi) or more between breeding and wintering areas. Those who have followed news of the Great Egrets that have been carrying GPS transmitters attached by Audubon Canyon Ranch’s conservation science team will know our local population can do the same. In the fall of 2018, one individual, referred to as GREG 10, flew down to Mexico, over 1,500km (932mi) from where he was banded on Tomales Bay.

What hasn’t been so well captured by scientific literature is the degree to which long-distance migration is (or isn’t) the default, a consideration that could influence the efficacy of conservation efforts. In coastal California, the number of Great Egrets present during the winter suggests there’s plenty of food available to them, and birds here aren’t faced with winters that freeze over the waters they forage in, as happens elsewhere. Until recently, no one knew if any birds from this population migrated at all.

Coastal Great Egrets use varied migratory strategies

Audubon Canyon Ranch’s conservation science team just published an article in Waterbirds showing that the Great Egrets they tagged on Tomales Bay displayed a range of migratory behaviors. Two individuals remained resident, never flying farther from Tomales Bay than those tending nests with chicks there had during the breeding season. Seven egrets migrated beyond the breeding area, but with a large variety of distances travelled—though one migrant egret avoided the coast during winter, preferring to forage in flooded fields and streams around Sebastopol and Santa Rosa, never exceeding 35km (22mi) from her nest site.

The same individual that made it as far as Mexico – GREG 10 – has remained on Tomales Bay since 2020, demonstrating that Great Egrets aren’t tied to a particular migratory mode for life.

A few previously published accounts suggested Great Egrets might migrate both during the day or at night but didn’t use tracking methods allowing a complete picture of the timing of their movements. Among the egrets in our study that migrated, we saw a range of behaviors, including an individual only making daytime migratory movements, and others making the majority of movements at night.

The variety of migratory behaviors we recorded is particularly interesting as Great Egrets are one of very few bird species that breed on every continent except Antarctica, inhabiting a wide range of ecosystems and seasonal weather patterns. As many Great Egrets breed in regions with habitat available year-round, we expect it might be quite common for other populations not to migrate, or to show a mixture of migratory and non-migratory behaviors as observed in this study.

Effective conservation requires a landscape-scale approach

Movements recorded by some of these tagged birds show that they depend on habitats beyond the Bay Area where we monitor breeding. Many migrant egrets in this study wintered in the Central Valley, along irrigation canals and waterways near commercial and residential development and farmland. This work reinforces the idea that conservation actions to protect Great Egrets must be applied at a regional, rather than simply local, scale for effective protection.

Full article available online at BioOne.org

The full article, coauthored by Audubon Canyon Ranch’s David Lumpkin (Avian Ecologist), Scott Jennings (Avian Ecologist), Nils Warnock PhD. (Director of Conservation Science), and Emiko Condeso (Ecologist/GIS Specialist), is available at https://doi.org/10.1675/063.045.0205